Scouts frequently update their maps

Scouts (those who are motivated to see things as they are, not as they wish they were) actively look for ways to update their mental maps with better information. This enables them to learn faster, tending to make them more innovative and more able (over time) to understand things as they are.

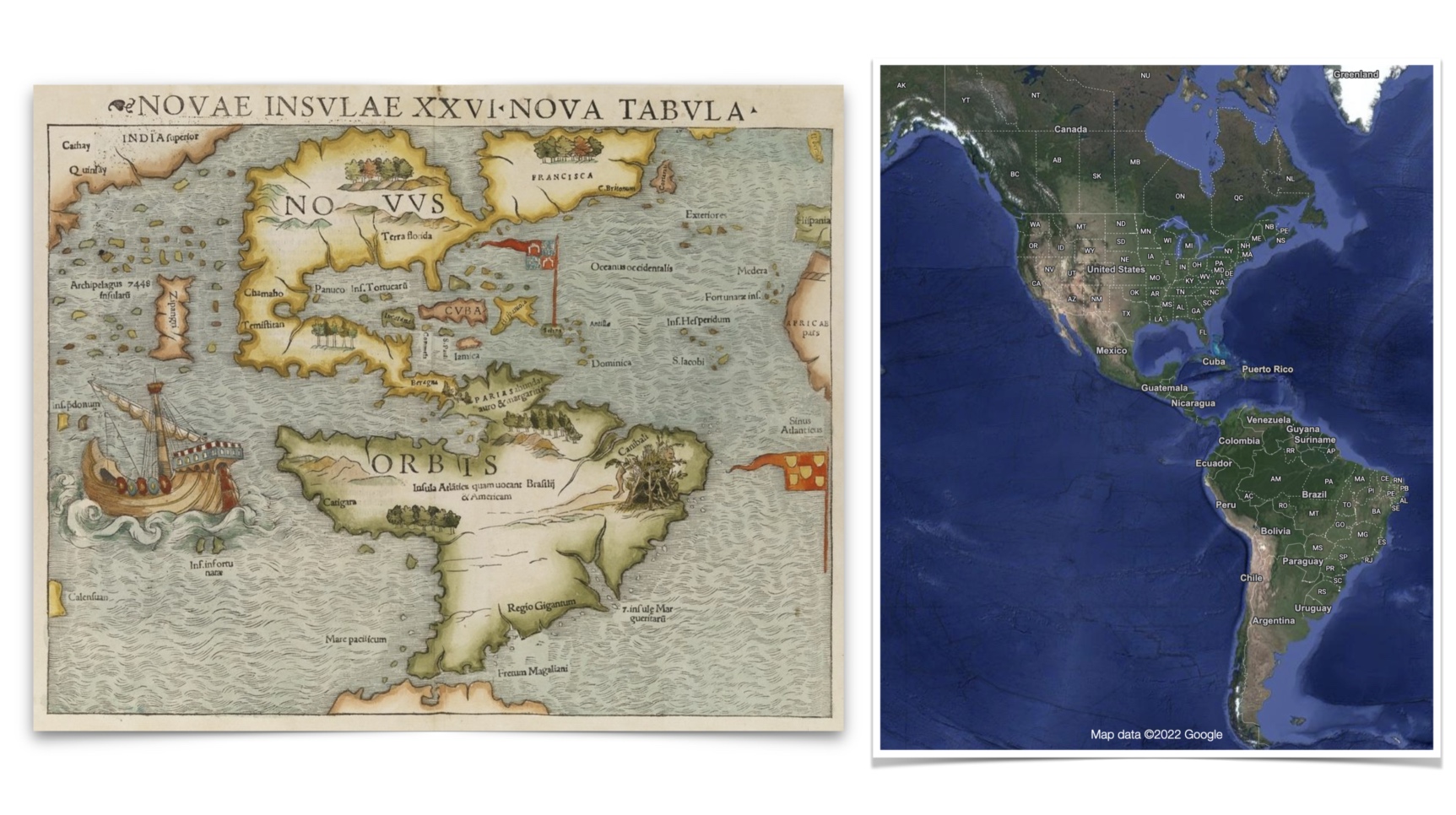

When early cartographers made maps of the so-called “New World” they were the best possible at that time—representing massive leaps forward in the advancement of knowledge. But two equal and opposite errors could be made once those first maps were constructed.

- The mapmakers could become enamored with the first maps and see no need to updated them—after all, people could sail ships by those maps and arrive more-or-less where they intended to.

- Later mapmakers could judge the earlier maps in light of contemporary technologies and knowledge and deride the first maps as primitive caricatures.

The solution to both is to acknowledge the value of the first maps in light of its own context, and then continue to update the maps to more closely align them with reality.

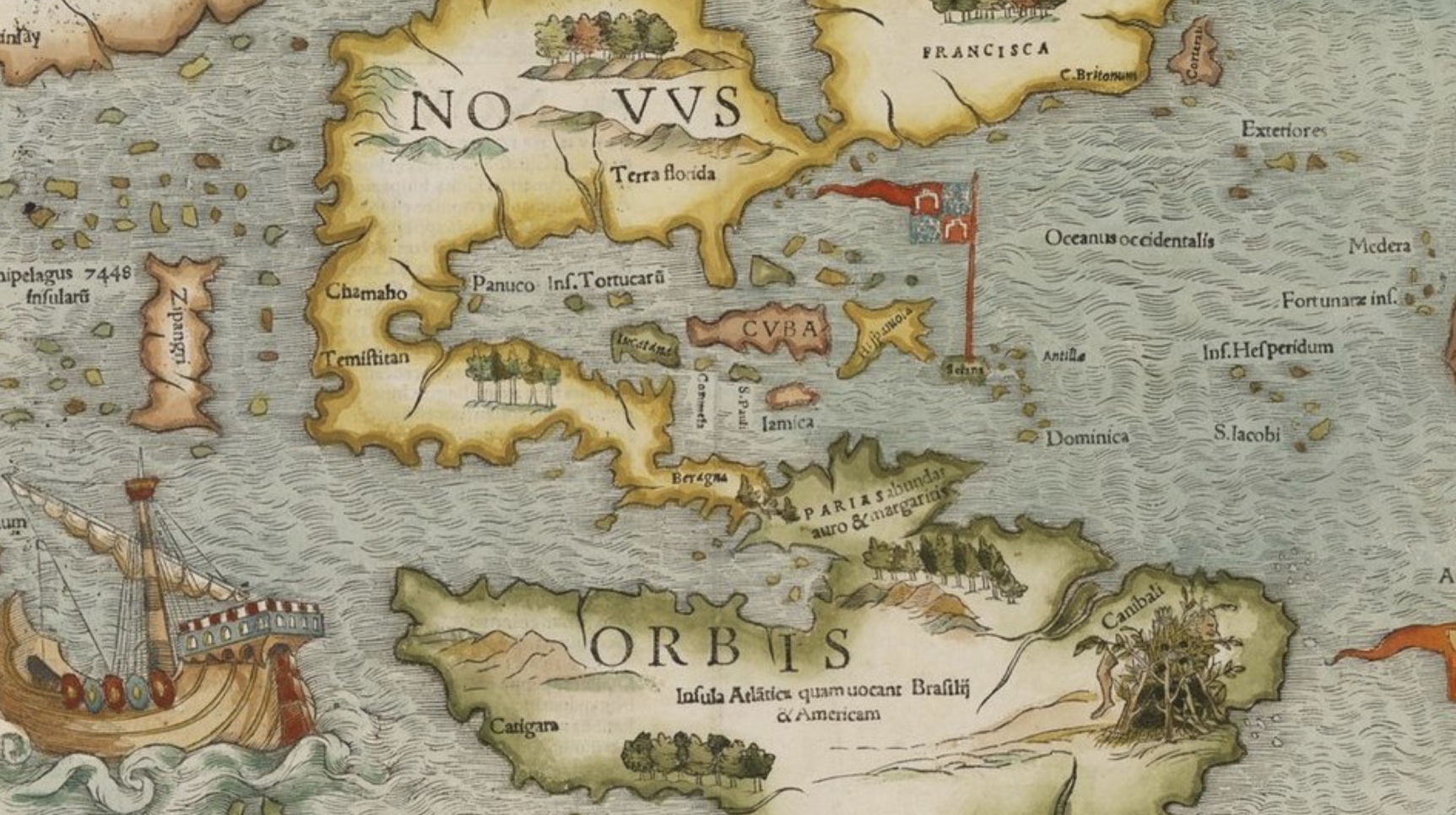

1540s: Münster’s Cosmographia – considered to be the first to show the entire continents of North and South America.

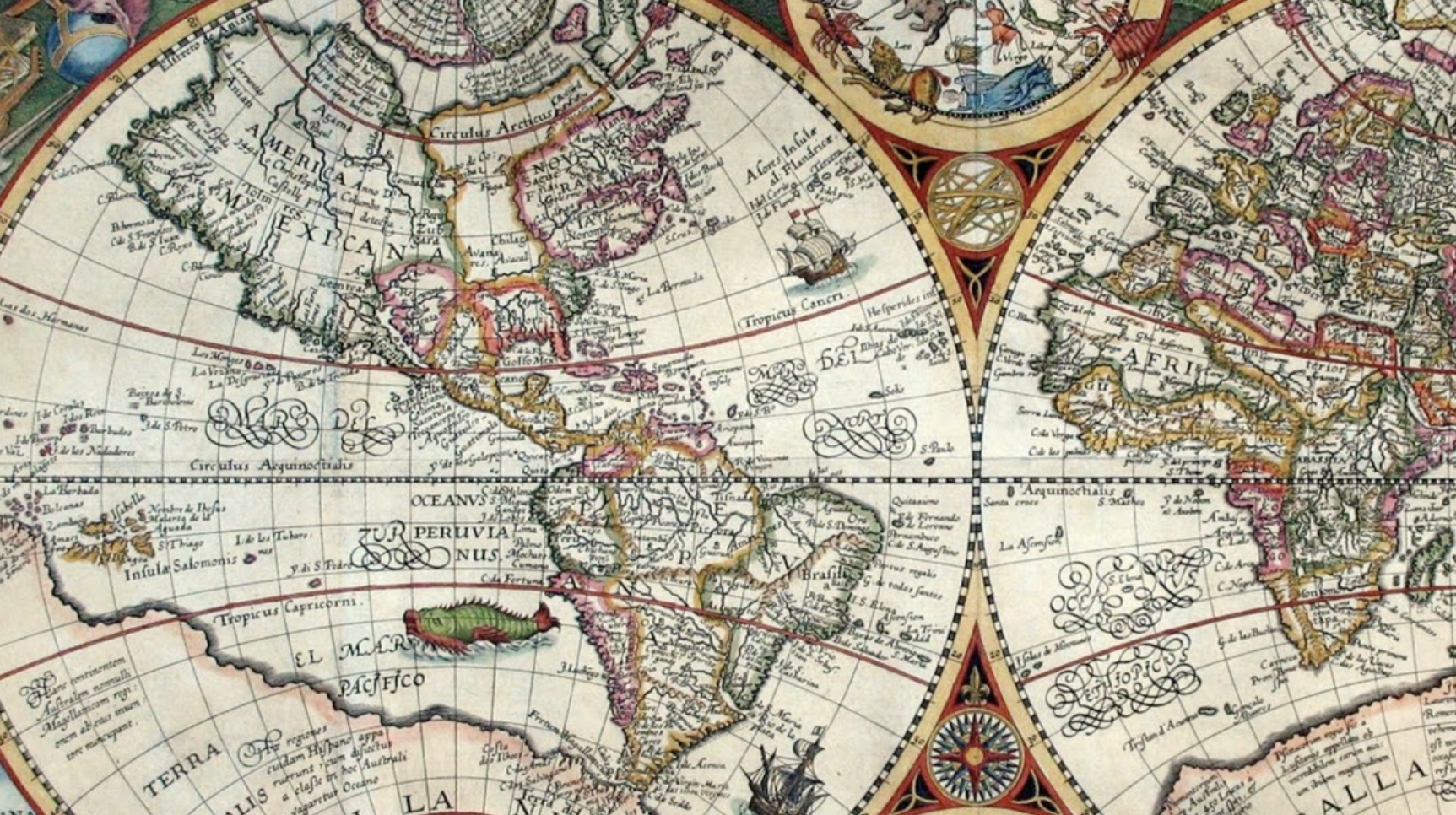

1594: Orbis Terrarum

Updating maps requires actively seeking out information that could indicate the map is inaccurate:

Seek out information that goes against your views. You can fight confirmation bias, burst filter bubbles, and escape echo chambers by actively engaging with ideas that challenge your assumptions. An easy place to start is to follow people who make you think—even if you usually disagree with what they think.[1]

Updating a map is not the same as admitting error.

…scouts think about error differently from most people. First, they revise their opinions incrementally over time, which makes it easier to be open to evidence against their beliefs. Second, they view errors as opportunities to hone their skill at getting things right, which makes the experience of realizing “I was wrong” feel valuable, rather than just painful.

…

The word admit makes it sound like you screwed up but that you deserve to be forgiven because you’re only human. It doesn’t question the premise that being wrong means you screwed up.

…

Scouts reject that premise. You’ve learned new information and come to a new conclusion, but that doesn’t mean you were wrong to believe differently in the past. The only reason to be contrite is if you were negligent in some way… But most of the time, being wrong doesn’t mean you did something wrong. It’s not something you need to apologize for, and the appropriate attitude to have about it is neither defensive nor humbly self-flagellating, but matter-of-fact.

…

Even the language scouts use to describe being wrong reflects this attitude. Instead of “admitting a mistake,” scouts will sometimes talk about “updating.” That’s a reference to Bayesian

…

You don’t necessarily need to speak this way. But if you at least start to think in terms of “updating” instead of “admitting you were wrong,” you may find that it takes a lot of friction out of the process. An update is routine. Low-key. It’s the opposite of an overwrought confession of sin. An update makes something better or more current without implying that its previous form was a failure.[2]

#strategic #strategic-cartography #cognition

See also:

- Tools both illuminate and limit our understanding

- Resources/Garden/The map is not the territory

- The clarity of a map is not easily distinguished from its accuracy

The Scout Mindset – Galef (2021) § “‘Admitting a Mistake’ vs. ‘Updating’” ↩︎