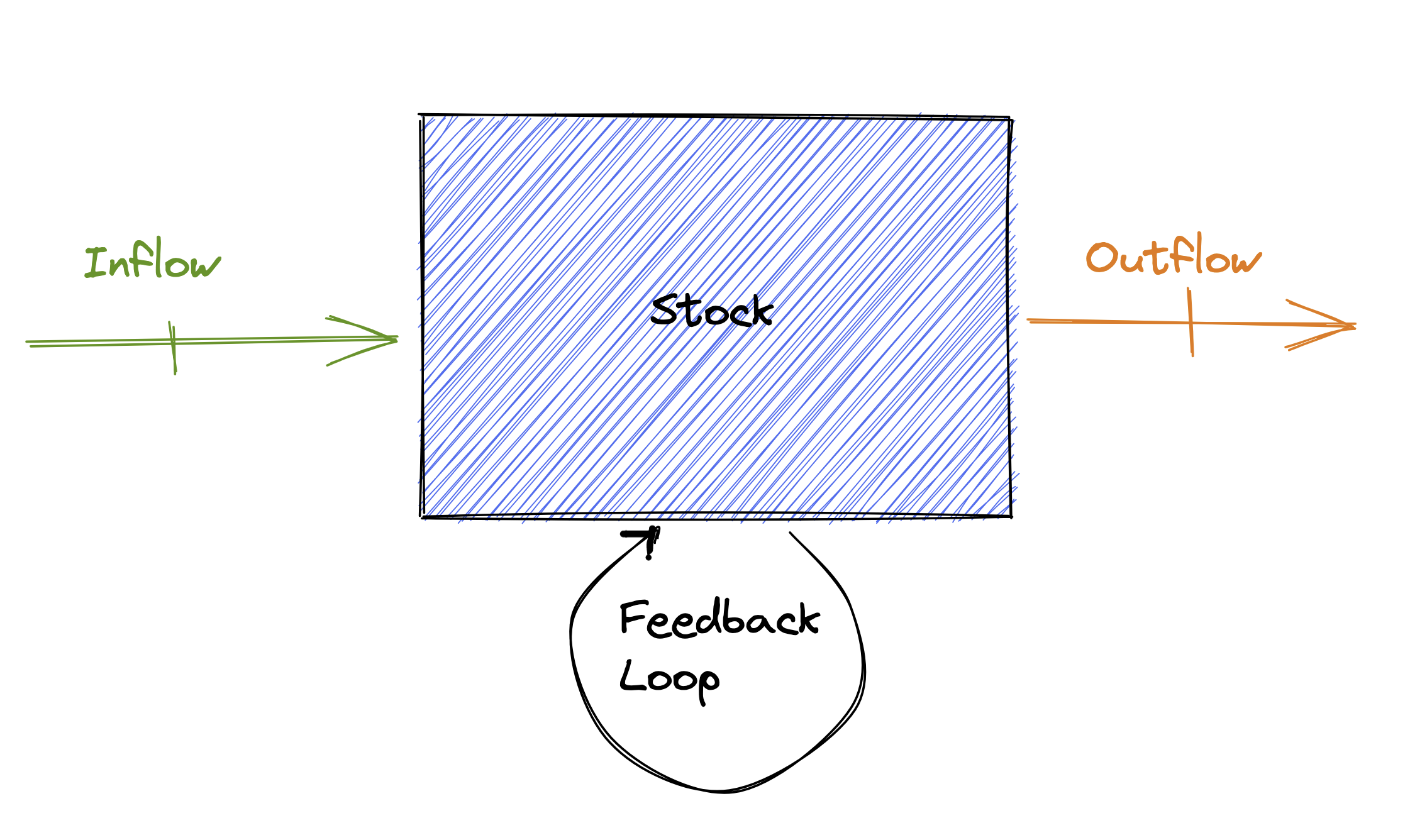

Systems Thinking perceives the relationships and structure of complex systems

The ability to perceive a complex system and understand the relationships between relationships of which it is comprised.

Bahcall differentiates between an “outcome mindset” and a “system mindset” (ie., Systems Thinking):

Teams with an outcome mindset, level 1, analyze why a project or strategy failed. The storyline was too predictable. The product did not stand out enough from competitors’ products. The drug candidate’s data package was too weak. Those teams commit to working harder on storyline or unique product features or a better data package in the future... Teams with a system mindset, level 2, probe the decision-making process behind a failure. How did we arrive at that decision? Should a different mix of people be involved, or involved in a different way? Should we change how we analyze opportunities before making similar decisions in the future? How do the incentives we have in place affect our decision-making? Should those be changed?[1]

McChrystal notes that NASA succeeded in sending men to the moon and back in part because they implemented systems engineering, built on Systems Thinking:

NASA leadership understood that, when creating an interactive product, confining specialists to a silo was stupid: high-level success depended on low-level inefficiencies. ... What Mueller instituted was known as “systems engineering” or “systems management,” an approach built on the foundation of “systems thinking.” This approach, contrary to Reductionism, believes that one cannot understand a part of a system without having at least a rudimentary understanding of the whole. It was the organizational manifestation of this insight that imbued NASA with the adaptive, emergent intelligence it needed to put a man on the moon.[2]

Note: Systems engineering means “understanding not only your own piece of the engineered product, but also how it fits with the other pieces and contributes to the product’s overall objectives.”[3]

Pink suggests that success in the Conceptual Age requires Systems Thinking:

The boundary crosser, the inventor, and the metaphor maker all understand the importance of relationships. But the Conceptual Age also demands the ability to grasp the relationships between relationships. This meta-ability goes by many names—systems thinking, gestalt thinking, holistic thinking. I prefer to think of it simply as seeing the big picture.[4]

See also:

- Systems Theory studies the relationships and structure of systems

- Systems Thinking perceives the relationships and structure of complex systems

- Systems mindset examines the quality of decisions, not just outcomes

- Complex systems exhibit emergent behavior

- Complex systems are characterized by VUCA

- Emergence is non-linear behavior of a system

Loonshots – Bahcall (2019), ch. 5, § “How to Win at Chess.” ↩︎

Team of Teams – McChrystal, et al. (2015), ch. 7, § “New Metal Alloys, Some of Which Have Not Yet Been Invented” ↩︎

The Three-Box Solution – Govindarajan (2016), ch. 2, § “Building New Box 3 Capabilities and Processes” ↩︎

A Whole New Mind – Pink (2006), ch. 6, § “Seeing the Big Picture” ↩︎